Award Metadata @ DataCite

/Ted Habermann, Metadata Game Changers

Cite this blog as Habermann, T. and Robinson E. (2025). DataCite Bright Spots. Front Matter. https://doi.org/10.59350/z0nex-23v25

Finding research objects that are related to a particular funder is one of the principal use cases for persistent identifier repositories in the global research infrastructure. Detecting objects related to funders is an important first step, but perhaps detecting objects related to specific awards is actually the “holy grail” of funder metadata. As is the case, by definition, holy grails are very difficult to find, and award metadata certainly falls into that category.

In this post we characterize the current state of funder and award metadata across DataCite and then explore metadata for resources funded by the U.S. National Science Foundation to understand more details. This work provides a context for future work exploring quality and consistency of award metadata in DataCite.

What is “Funder Metadata”

Several authors have explored availability of funder metadata in various repositories. For example, Kramer and De Jonge (2022) tracked down publications funded by the Dutch Research Council in several repositories. They focused on funder names and identifiers and found that 53% of the resources funded by the Dutch Research Council NWO had funder names and 45% had funder identifiers.

Crossref provides a set of summary statistics that lists the overall number of unique DOIs with fundRef data as just under 3 million. Given that there are over 119 million journal articles, ~2.5% have some fundRef metadata. Kramer and De Jonge, 2022 and Jones and Habermann, 2024 showed that this has changed significantly through the history of Crossref. Since 2018 the average completeness for funder names has been between 20 and 25%.

This work focuses on DataCite, so “funder metadata” is defined in terms of the DataCite Metadata Schema. It has been held in the fundingReference property since the introduction of V4.0 of the schema during 2016. This object has six sub-properties:

"fundingReferences": [

{

"awardTitle": "EAGER: INFORMATE: Improving networks for organizational

repositories through metadata augmentation, transformation and evolution",

"funderName": "U.S. National Science Foundation",

"awardNumber": "2334426",

“awardUri”: “https://www.nsf.gov/awardsearch/showAward?AWD_ID=2334426”

"funderIdentifier": "https://ror.org/021nxhr62",

"funderIdentifierType": "ROR"

}]

and multiple funders can be associated with each DOI.

Award Metadata

Identifying funder awards related to papers, datasets, projects and other research objects is an elusive challenge at the bleeding edge of global research infrastructure development and analysis. While we are making progress identifying objects themselves with DOIs, people with ORCIDs iDs, and organizations and funders with RORs, consistent identification of awards remain elusive.

There are two kinds of errors that might occur at various points along this journey:

1. errors of omission occur when items are left out

2. errors of commission occur when an incorrect value is let in.

Table 1 illustrates these two types of errors. DOI A shows an error of omission as the funder identifier and award number are missing, i.e., they have been omitted. DOI B is funded by two awards. The metadata for the first award is complete and appears to be correct, the identifier and award number both match the pattern expected for the U.S. National Science Foundation. The second award appears complete, but the identifier does not match the funder name or the form of the award number. It appears that an incorrect identifier has been added to the record, an error of commission.

Table 1. Errors of omission and commission in funder metadata.

Problems with funder metadata are partially due to the tortuous data journey that awards must traverse on the way into the infrastructure. Figure 1 shows this journey schematically. It begins with a funder granting an award with an identifying number, typically unique within the funder namespace. Research ensues and, after some time, research outputs are created with funding metadata either in free text in an acknowledgement section or in a submission system input. The first gate on the journey is the format of this free or input text, A in Figure 1.

Even though many funders and research organizations encourage authors to write acknowledgements in a standard way, they end up in many different forms. This can make interpretation of the information difficult and error prone. In many case the funding information is inherently complicated with multiple awards for different authors identifier by subscripts or initials, multiple awards for the same authors, award numbers for different funders intermingled, etc.

Figure 1. The award journey to the global research infrastructure. A-C indicate gates along the journey that can act as obstacles to funder metadata along the way.

The second step in this journey involves interpreting the free text and converting it to structured metadata elements (B). The narrow arrow at B reflects the fact that only a very small amount of funder metadata makes it through this gate. This is reflected, for example, in the report that only 1% of the metadata records in Crossref have award numbers (Pedraza, R. G., & Tkaczyk, D. 2025). The funder name and award number extracted from the full text are minimum metadata for describing the award and they are many times the only items included in acknowledgments and, therefore, in the initial metadata.

The importance of globally unique persistent identifiers (PIDs) for funders has been known for over a decade (Bilder, 2014) and extending this idea to include award numbers is currently in progress (French et al., 2023). Currently, identifiers for funders can be retrieved from the Research Organization Registry (ror.org) and expressed as a ROR, i.e. https://ror.org/021nxhr62 for the U.S. National Science Foundation. Award titles and other details can be retrieved from the NSF Award Search, the HHS Tracking Accountability in Government Grants System (TAGGS), or other funder specific systems, C in Figure 1. These retrievals must be done correctly to avoid errors of commission.

The journey depicted in Figure 1 is schematic and idealized. In a perfect world, contributions by funders like the U.S. National Science Foundation can be detected accurately, the final green arrow in the award journey. In the real world, the gates open and close over time, priorities of people and organizations shift, and systems evolve, all of which add uncertainty and unknown changes into the picture. A real-world example can help us understand how these complexities might be reflected in the data.

The Real World

In this work we focus on DataCite metadata which are created and managed directly by research institutions. The complication of variations introduced in the journal layer are out of scope, i.e. left as a target for future work. This may also increase the chances that problems identified here can be corrected because the complexity of journal submission and processing systems does not need to be considered.

How Much Funder Metadata are There?

As is clear in the metadata journey depicted in Figure 1, even this fundamental question can be answered in several ways. Some answers can be readily retrieved using simple queries in the DataCite API. The total number of DataCite DOIs has recently passed 100 million with over 27 million records (27%) coming from the Japanese National Institute for Fusion Science (NIFS). These are among the most complete metadata in DataCite (Habermann, 2025 and Wimalaratne, S., & Nakanishi, H. (2025)) and they all include complete funder metadata, so they skew the big picture. Table 2 shows the overall DataCite numbers with the NIFS records removed. The amount of funder metadata in the rest of DataCite is consistent with the low numbers reported recently for Crossref and supports the thin gate at B in Figure 1.

Table 2. DataCite funder metadata counts retrieved Oct. 16, 2025. Add https://api.datacite.org/dois? and “%20NOT%20client-id: rpht.nifs&page[size]=1&disable-facets=true to retrieve data using the DataCite API. These numbers exclude over 27 million records from the Japanese National Institute for Fusion Science, all of which have complete funder metadata. The has-funder criteria is defined by DataCite as records with funderIdentifierType = Crossref Funder ID.

Funder metadata remains rare in DataCite metadata, as is true for many of the recommended and optional elements (funder metadata is optional in the DataCite schema documentation). Nevertheless, a population of several million current records in DataCite is large enough to explore and start to characterize the transitions shown in Figure 1.

It is interesting to note that funder names and award numbers are the most common funder metadata components. This is consistent with the general observation that these are the most common elements included in the free text metadata provided by researchers in Step A (Figure 1).

The U.S. National Science Foundation is one of the most common funders in DataCite so the number of records funded U.S. NSF is likely large enough to surface errors that might happen along the data journey, so this funder is the focus for the next section.

U.S. National Science Foundation @ DataCite

Research outputs in DataCite funded by the U.S. National Science Foundation (USNSF) are a reasonable example for exploring the current state of funder metadata for several reasons. First and foremost, USNSF is one of the most common supporters of research across a wide variety of domains, so metadata for many thousands of outputs are available. This sample is large enough to improve the chances of sampling the diversity of problems that might occur.

There are several approaches to finding resource objects in DataCite funded by the U.S. National Science Foundation. The most straightforward is using the API query fundingReferences.funderName:”National Science Foundation”. Funder metadata counts for records with a funderName that includes “National Science Foundation” are shown in Table 3. These numbers are retrieved using the DataCite API, so the units are records. This dataset is referred to here as the USNSF dataset. The big three funder elements, funderNames, awardNumbers, and funderIdentifiers will be explored below.

Table 3. Numbers of records in DataCite with "National Science Foundation" as the funderName with records counts retrieved by the DataCite API on October 17, 2025.

Table 3 shows that funderNames are the most common funder metadata element found for the USNSF in DataCite. As discussed above, the traditional source of most of these names has been free text in uploaded metadata files or in submission forms. This is changing as the DataCite form for creating metadata (Fabrica) evolves to facilitate automatic funderIdentifier detection, definitely a step towards unambiguous identification of funders.

The USNSF data includes 3677 unique funderNames that occurred over 62,000 times. The name “National Science Foundation” was used to select the data and it occurred just over 47,000 times in 31,778 records, reflecting the fact that DataCite DOIs can have multiple funders and awards. Twenty-two other funderNames occurred over 100 times each (Table 4). These are organizations that funded work jointly with USNSF. Being able to identify collaborations between different organizations is an important benefit of unambiguous identifiers in the metadata.

Table 4. Names of organizations that co-funded over 100 research outputs with USNSF.

FunderNames that begin with “National Science Foundation” can also include other information like programs, partner names, or award numbers. This extraneous information can make it more difficult to identify outputs and connect them with the correct funders.

Table 5. FunderNames that begin with National Science Foundation in the USNSF dataset. While the simple name “National Science Foundation” is by far the most common, these demonstrate the kinds of variations that can occur. A number of these names contain asterisks which are from the originals.

Ninety-two percent of the records with funderNames also have award “numbers”. Like funder names, the award number contents vary widely. Some are simply seven-digit numbers, the current format for NSF award numbers, some include abbreviations for NSF Divisions or Programs, some are long lists of award numbers, and some are free text with embedded award numbers.

Much of this variation in award numbers is related to the diversity of funders in the data as many of them, like USNSF, have their own format for award numbers. For the USNSF awards, 98% could be matched with a regular expression that accounted for the Division / Program abbreviations and the award numbers made up of seven digits or two digits for a year followed by a dash and five digits, both standard forms for NSF award numbers in the past. This matching approach yields a good first approximation to USNSF award recognition with 98% of the award numbers for the funder National Science Foundation matched.

Table 5 shows funder identifiers that are associated with the simple funderName = “National Science Foundation”. These occur in 79% of the USNSF records. The two most common funder identifiers are either the complete or identifier only versions of the USNSF Crossref Funder ID and ROR. The total counts of these two are very close, with Crossref Funder ID ahead by just over 2,600. This reflects the long history of almost 7,000 Crossref Funder IDs between 1980 and 2011, before the first ROR occurred in the data.

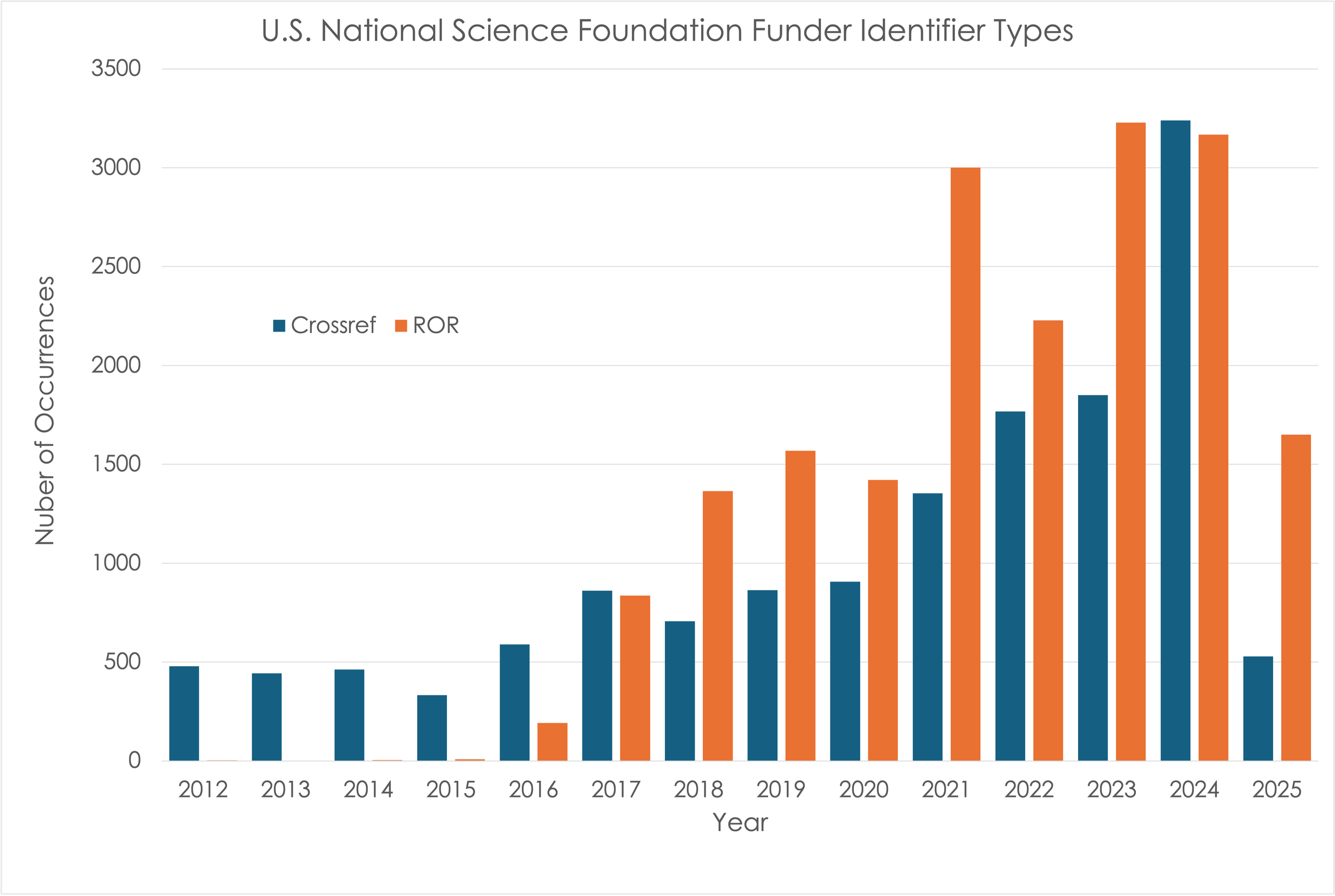

The landscape of funderIdentifiers has changed significantly over the last several years with the announcement that the Crossref Funder IDs are being deprecated to be replaced by RORs, French et al., 2023. Figure 2 shows the yearly number of Crossref Funder IDs and RORs in the USNSF dataset. RORs have outnumbered Crossref Funder IDs every year since 2018 except 2024, showing that the transition is well underway. Nevertheless, searches using funderIdentifiers must still use both for a more complete result.

Figure 1. Counts of Crossref Funder IDs and RORs for the U.S. National Science Foundation in DataCite.

The Global Researcher ID (GRID) for the U.S. National Science Foundation (grid.431093.c) occurs nearly 100 times in this dataset. GRIDs were created by Digital Science, provided as the initial set of organizations included in ROR during 2019, and deprecated during 2021 (ROR Leadership Team, 2021). The GRIDs in this dataset are from a single Data Repository, reflecting the challenges repositories can face as the identifier landscape evolves. All three of these organizational identifiers, and others, are included in and can be searched for in the ROR repository.

Table 5 includes several funder identifiers that do not resolve to the U.S. National Science Foundation, the most common being https://doi.org/10.13039/501100008982 which is the Crossref Funder ID for the National Science Foundation of Sri Lanka. Unfortunately, this organization shares the acronym “NSF” with the U.S. National Science Foundation, as do several others (Schwarzman and Dineen, 2016). This has led to many cases of funder misidentification (Habermann et al., 2024). Note the occurrence of 86 records with funderName = National Science Foundation of Sri Lanka in Table 5 another indicator of potential problems.

It is interesting to note that 359 of the 456 occurrences of the Sri Lanka identifier are during 2017, the first year it occurs. The occurrences of this organization in Crossref, viewed through the DataCite Commons, also shows a strong initial peak between 2018 and 2020. This suggests that this may initially have been related to a software bug somewhere along the data journey that was identified and fixed. If so, it is clear that the effects of this bug have persisted along with the incorrect persistent identifiers. Identifying and documenting these potential errors of commission remains for future work.

Award Bright Spots

As shown in Figure 1, awards numbers in DataCite metadata start with researchers and repositories working together to identify awards and build complete funder metadata through the initial curation process. One of the goals of this work is to find bright spots, i.e. repositories that provide good examples and lessons that the community can learn from. There are several ways to identify award bright spots:

· The most cited U.S. National Science Foundation award in DataCite is 1326927 (or OCE-1326927), titled “Management and Operations of the JOIDES Resolution as a Facility for the International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP)” and awarded to the Texas A&M Research Foundation. This award is cited 1,676 times for datasets in Zenodo (1,659) and PANGEA (17).

· The repository with the most award numbers is Dryad, with 5,043 National Science Foundation award numbers cited almost 9,000 times.

· Other notable repositories are the Antarctic Meteorological Research and Data Center Repository at the University of Wisconsin, the National Ecological Observatory Network at Battelle Memorial Institute, the Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research at the University of Michigan, and the Syracuse University Qualitative Data Repository.

All of these repositories have found ways to work with their communities to ensure that funders that support the research are recognized and discoverable. We have a long way to go, and these bright spots are helping to lead the way!

Conclusion

Awards are a critical metadata element that helps the community identify and discover the contributions of organizations that support research across many scientific domains. Ensuring that these metadata are available and accurate is the responsibility of the researchers that receive support and the repositories that work with them to share their results, data, and other outputs.

The journey that award metadata make from researchers through a variety of systems and into repositories includes many transitions and obstacles that can prevent success. These difficulties are reflected in the small number (< 3%) of research outputs that currently include award metadata. In this work we focused on these errors of omission – finding missing information. Errors of commission, i.e. incorrect metadata, also exist for funderIdentifiers and awardNumbers. These will be the focus of future work.

The U.S. National Science Foundation is an important funder across a broad spectrum of scientific domains. Metadata for outputs they have supported provides a sample for exploring characteristics of funder metadata in DataCite. FunderNames are the most common funder metadata included in DataCite, and most records with funderNames also include awardNumbers (91%) and funderIdentifiers (79%). All three of these elements show variations in format and content that need to be addressed prior to analysis and edge cases still contribute uncertainty to the results.

The transition from Crossref Funder IDs to RORs for identifying the U.S. National Science Foundation is making progress for new identifiers, but Crossref Funder IDs are still being added to recent metadata, and a significant historic backlog persists. The integration of RORs into automated funder selection interfaces will likely help facilitate this transition, but careful analysis of the automated selections must be done to catch and correct errors.

Some research organizations and repositories are doing well creating and curating funder metadata through the journey into the global research infrastructure. These provide examples that all of us can learn from as we work to acknowledge funders throughout this connected network.

References

Bilder, G. (2014). ♫ Researchers just wanna have funds ♫. Front Matter. https://doi.org/10.64000/6fp15-79a77

Crossref (2025), Funding data overview, https://www.crossref.org/documentation/funder-registry/funding-data-overview/, accessed October 16, 2025.

French, A., Hendricks, G., Lammey, R., Michaud, F., & Gould, M. (2023). Open Funder Registry to transition into Research Organisation Registry (ROR). Crossref. https://doi.org/10.64000/v3429-p781

ROR Leadership Team. (2021). ROR and GRID: The Way Forward. Research Organization Registry (ROR). https://doi.org/10.71938/4JRG-4E16

Habermann, T. (2025). How Many When (2025 Update): Dataset bright Spot in the Driver’s Seat. https://doi.org/10.59350/5p6kw-j0740

Habermann, T., Jones, J., Ratner, H., Packer, T., (2024). Funder Acronyms Are Still Not Enough. Front Matter. https://doi.org/10.59350/cnkm2-18f84

Jones J, Habermann T. (2025). Leveraging the global research infrastructure to characterize the impact of National Science Foundation research. Information Services and Use 45(1-2):30-47. doi:10.1177/18758789251336079.

Kramer, B., & De Jonge, H. (2022). The availability and completeness of open funder metadata: Case study for publications funded by the Dutch Research Council. MetaArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31222/osf.io/gj4hq

Pedraza, R. G., & Tkaczyk, D. (2025). Piecing together the Research Nexus: uncovering relationships with open funding metadata. Crossref. https://doi.org/10.64000/607z6-1nh09

Schwarzman AB, Dineen MS. Identifying and Standardizing Funding Information in Scholarly Articles: a Publisher's Solution. In: Journal Article Tag Suite Conference (JATS-Con) Proceedings 2016 [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Center for Biotechnology Information (US); 2016. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK350153/

Wimalaratne, S., & Nakanishi, H. (2025). Scaling for Impact: How NIFS and DataCite Are Advancing Global Discoverability of Japanese Research. DataCite. https://doi.org/10.5438/44EW-F262