Universities@DataCite

/Cite this blog as Habermann, T. (2022). Universities@DataCite. Front Matter. https://doi.org/10.59350/sgzhr-3kk88

Introduction

I recently attended the Open Repositories Conference and learned quite a bit about repository tools being used by universities and other organizations. University repositories are particularly interesting to me as I am working on the Realities of Academic Data Sharing project with the Association of Research Libraries and several universities. A recent blog post compared DataCite metadata from institutional repositories and other general repositories. The metadata journeys from the researchers to the global infrastructure vary in these cases and this effects the FAIRness of the metadata. That work included only a small sample of universities and I wanted to extend it across a broader sample to try to characterize universities in DataCite generally. This is the first blog in a series describing what I found.

The initial sample included repositories with “University” or “College” (in several languages) in their names augmented with repositories associated with members of the Association of Research Libraries. This sample, termed University Repositories, included 458 repositories from all over the world and seemed to provide a good start for discerning overall characteristics of university repositories.

ResourceTypes

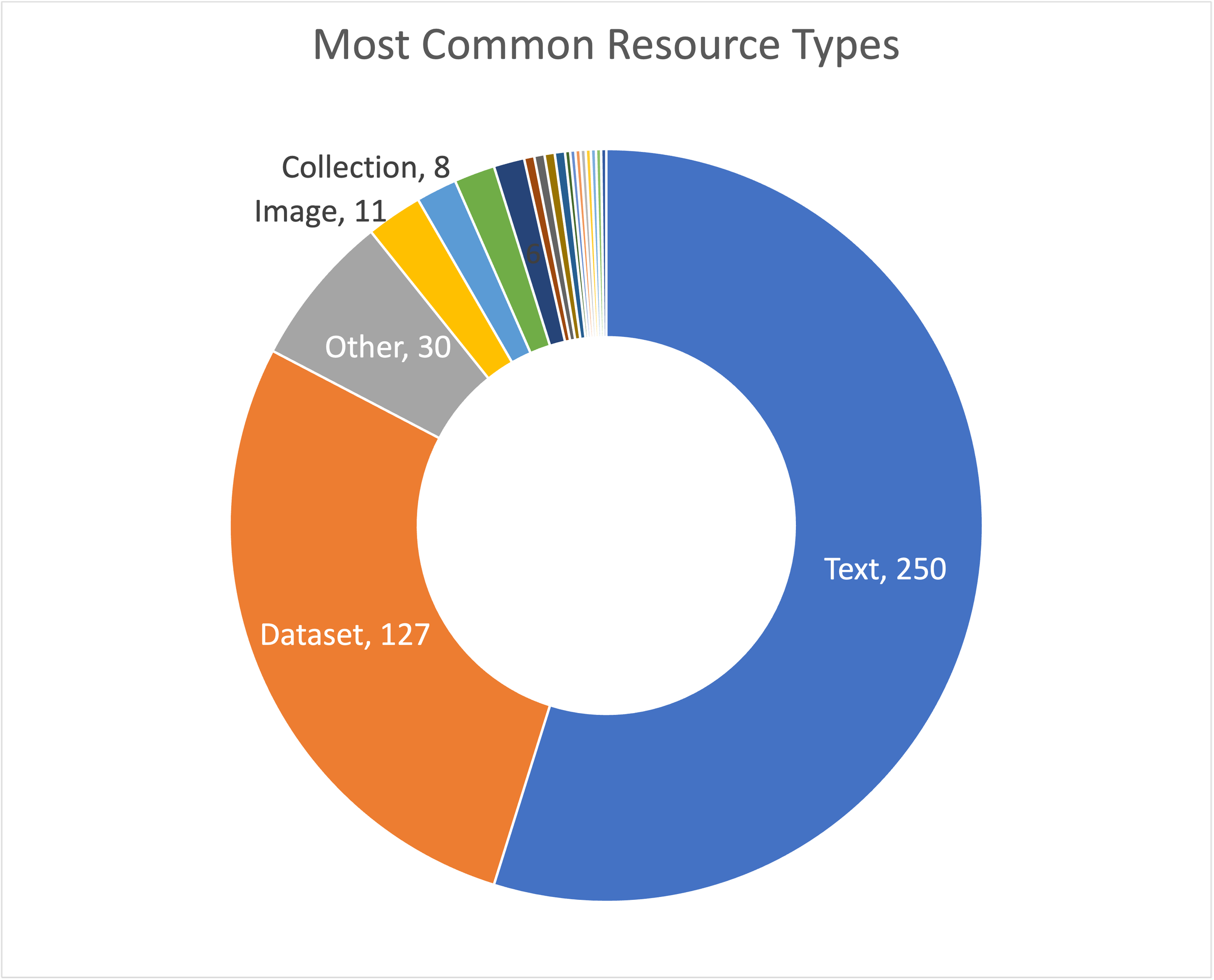

It is not uncommon to think about DataCite as the place where members register datasets for DOIs. Recent work reminded me that DataCite is also used to register DOIs for many other resourceTypes. In particular, “Text” resources are very common in DataCite and have outnumbered Datasets overall in many recent years. Figure 1 shows the distribution of resourceTypes in the University Repositories. Text resources clearly dominate the University Repositories. They make up ~1.4 million of the ~3 million resources (46%) while Datasets make up 25% of the resources (nearly 800,000). As a “Data Person” this observation takes some getting used to, but “it is what it is”!

Figure 1. Distribution of resourceTypes in University Repositories.

Most Common Resource Types

The distribution of resourceTypes across all University Repositories in Figure 1 shows that universities are using DataCite to register many kinds of objects. Many of these universities are DataCite consortia that manage multiple repositories, and it seems possible that, in some cases, different repositories within the same consortium might specialize in different resourceTypes. To find these specialized repositories I counted the number of each resourceType in each repository. Figure 2 shows the distribution the most common resource type in all the repositories. As might be suspected, the most common repository type is Text.

At this point, I am most interested in data, and DataCite repositories that specialize in data. To find these, I used two criteria: 1) repositories with the most common resourceType = Dataset and repositories with more than 100 datasets. These criteria selected 80 repositories. A random sample of 500 records was collected from each repository for a total of 29,838 records. Forty-four of the repositories had more than 500 records so the sample size of 500 resulted in 36 complete repositories being included in the sample.

Figure 2. Distribution of most common resourceTypes in University RepositorieS

Resource Author Affiliations

Affiliations are important for authors and contributors, as they make it possible to identify resources created by and contributed to by faculty members and associates of a particular university. The DataCite metadata schema has included affiliation names since Version 3.1 (2015) and identifiers for the affiliated organizations were added in Version 4.3 (2019). In this work I focused on author affiliations as they are much more common than contributor affiliations. Note: to see the affiliation data in the REST API a special parameter (affiliation=True) must be added to the request.

The metadata records retrieved in the sample (see description above) were examined to identify repositories that included affiliation information for creators. In all, 10,561 of 29,838 records in the overall sample (35%) included author affiliations and 61 of the 80 repositories (76%) included affiliation information for some records.

Two patterns emerge in these observations. Twelve repositories include just one affiliation, typically, the home affiliation of the repository, repeated multiple times. The other repositories include more than one affiliation. Typically, the ‘home’ affiliation is most common, but others are also included.

The observation of a single affiliation occurring many times in a repository was discussed in How Many RORs Do We Need? And the concept of Homogeneity Index was introduced as a way to measure this phenomena. It is calculated as

the number of records with the most common affiliation the total number of records

with a range from 0 to 1. If this index is close to 1, it means that a small number of affiliations are used many times in the repository, i.e. the affiliations are homogeneous. The index gets closer to 0 as the number of affiliations increases. Some examples demonstrate this concept.

In the first case, the University of Hong Kong has 135 affiliations in the 500 record sample. One hundred and thirty-three of these are the same: “University of Hong Kong” giving a homogeneity index of 133/135 = 98.5%, a very homogeneous affiliation list.

| Repository | Affiliation | Count |

| figshare.hku Two affiliations HI = 133 /135 = 98.5% | University of Hong Kong | 133 |

| London School of Economics and Political Science | 2 | |

| bl.kcl Five affiliations HI = 35 / 51 = 69% | King’s College London | 35 |

| University College London | 6 | |

| University of Winchester | 4 | |

| Institute of Enzymology | 2 | |

| Budapest University of Technology and Economics | 2 | |

| bl.standrew HI = 494 / 2064 = 24% | The University of St Andrews | 494 |

| 250+ other affiliations | 250+ |

Table 1. Affiliation homogeneity in university repositories.

In the King’s College case, the repository includes five affiliations in 49 of the 500 records in the sample. The most common affiliation, “King’s College London”, occurs 35 times = 69%. In the final example, the University of St. Andrews repository includes 2064 affiliations in 392 of the 500 records. In this case, the most common affiliation, “The University of St. Andrews”, occurs 494 times, 24%. The repository includes over 250 other affiliations, a very heterogeneous affiliation list.

In some cases, the ‘home’ institution occurs several different ways. For example, the most common affiliations in the repository for University of St. Andrews include two versions of the University name as well as names of two schools in the University:

| Affiliation | # Occurrences |

| The University of St Andrews | 494 |

| School of Chemistry | 329 |

| School of Physics and Astronomy | 288 |

| University of St Andrews | 235 |

Table 2. Common affiliations from the bl.standrew repository.

The occurrence of multiple names for the same University in affiliation strings is not unusual, in fact, disambiguating these cases is a primary reason for the development of unique and permanent identifiers for organizations (https://ror.org/02wn5qz54 in this case).

Affiliation Identifiers

The critical role of organizational identifiers in metadata in the academic recognition process has been discussed extensively during the last several years as has the importance of identifiers in addressing FAIR data principles. The previous section showed that affiliations, i.e. the foundation for connecting research results to universities, are rather sparse, occurring in ~34% of the records. The need for identifiers for these organizations was recognized only recently, so they are even less common. Only 704 of the 2,679 organizations in the sample are identified and these identifiers are used 6,216 times in 37 of the repositories. The repository identifier types are evenly spilt between RORs and GRIDs.

Organizational Connectivity

The concept of connectivity for individuals and organizations was introduced and discussed in a series of blog posts last year. Connectivity can be measured as the % of items in a repository that have identifiers, typically ORCiDs for individuals and RORs, GRIDs, or some other identifier for organizations. That work focused on one domain repository (UNAVCO) to explore the benefits of the communities built around domain repositories. Organizations and individuals that participate in these communities make multiple contributions so identifiers, once found, can be used multiple times.

University repositories seem similar to domain repositories except those participants are held together by the institution rather than by a specific domain. Can the same approach be used to improve connectivity for university repositories?

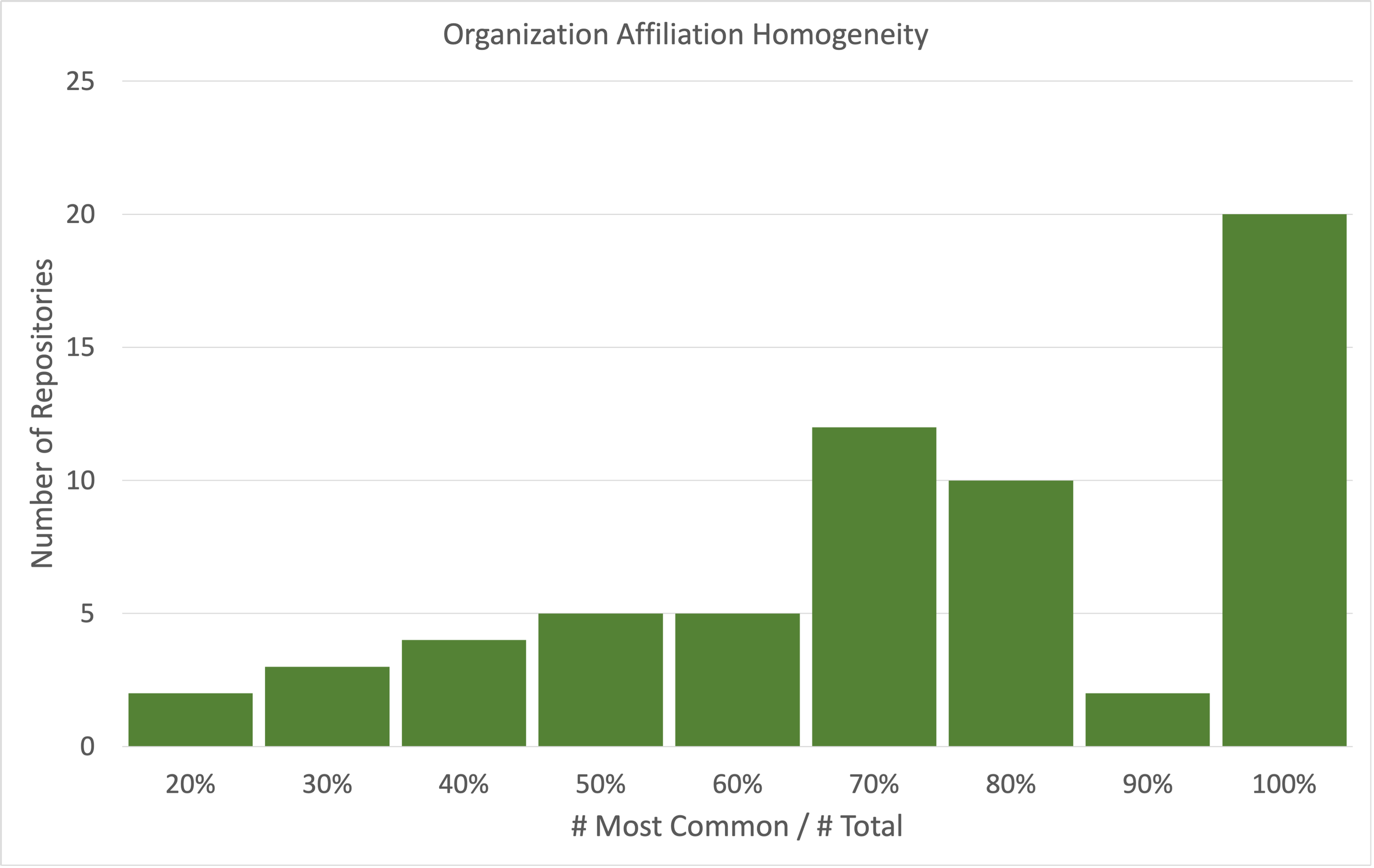

The affiliation homogeneity data discussed above indicates that the many university repositories have very homogeneous affiliations, i.e. most of the affiliations in the repository are the same. Figure 3 shows the Homogeneity Index for 63 repositories with affiliations. The data shows that for 20 of the repositories a single affiliation covers over 90% of the records with affiliations.

Figure 3. Affiliation homogeneity in university repositories.

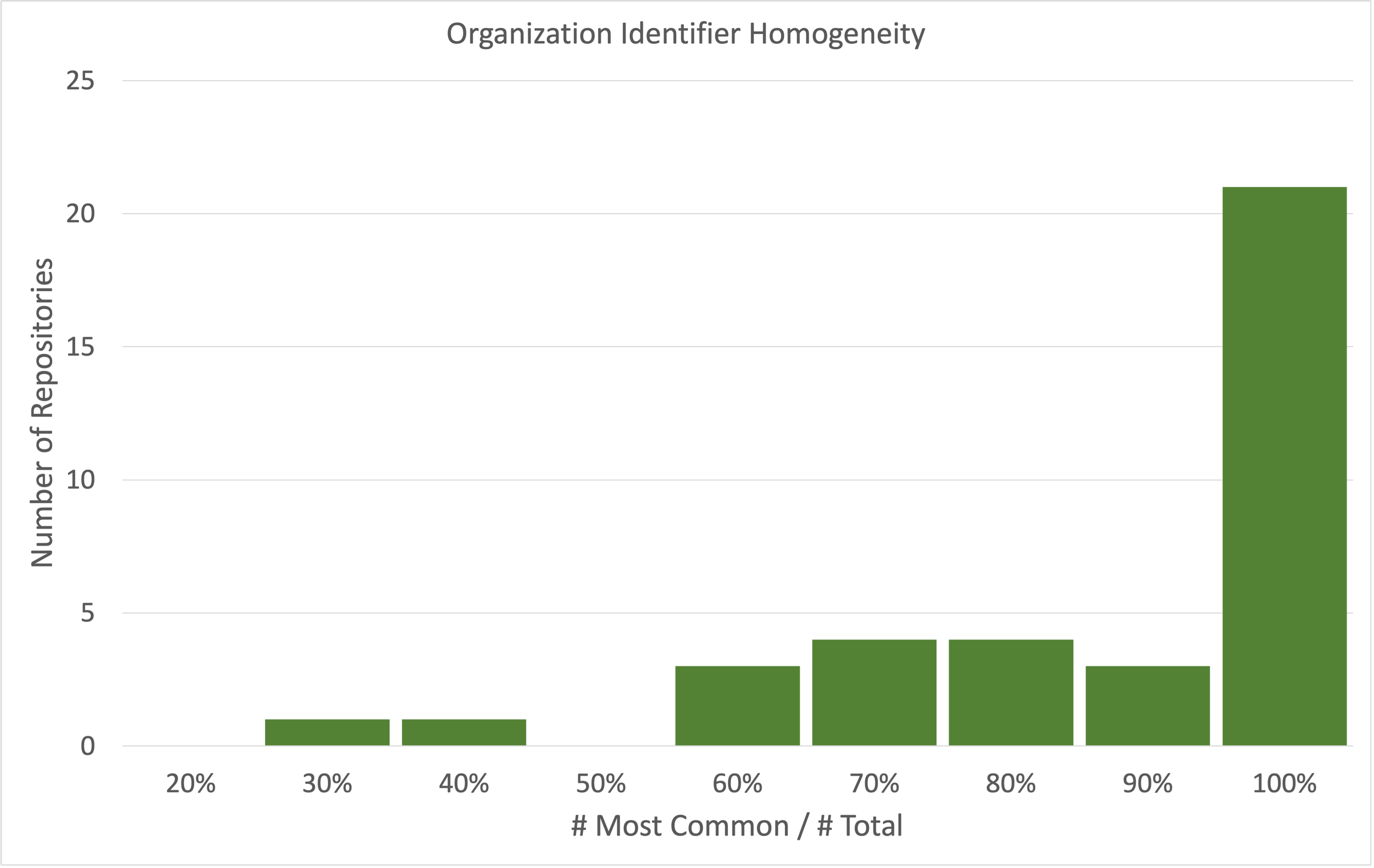

Figure 4 shows the distribution of organizational identifier homogeneity across the 37 repositories that have organizational identifiers. The pattern is similar, i.e. most repositories only include a single identifier, that is the identifier for the institution that manages the repository.

Figure 4. Affiliation identifier homogeneity in university repositories.

Together these data show that most university repositories currently have very homogeneous affiliations and organizational identifiers. This is not surprising as these repositories principally serve researchers in their institutions as authors. At the same time, many research objects are created by researchers from multiple institutions. These data can provide some insight into how identifiers can be used as an indication of collaboration across multiple universities and, therefore, to populate connections in the PID Graph.

Figure 5 compares the number of affiliations in the university repositories with the number of organizational identifiers as green boxes. If all affiliations were accompanied by identifiers, the green boxes would fall on the dashed line of equality (true for 22 of the repositories with identifiers). Repositories without identifiers appear as boxes on the x-axis.

The red diamonds show the number of occurrences of the most common identifier in the repository, typically the hosting institution. The difference between the green boxes and the associated red diamonds is the number of identifiers in each repository for collaborating institutions.

For example, the repository with the most identifiers (1262) is the University of California, Davis (UCD, cdl.ucd). Of these, 795 are https://ror.org/05rrcem69, the ROR for UCD, identified as “Hosting Institution”. The other 467 identifiers are from 228 other organizations, identified as “Collaborators”. A second example is the University of Leeds (bl.leeds) with 472 occurrences of https://ror.org/024mrxd33, the ROR for the University of Leeds, and 120 other identifiers.

Conclusion

DataCite is used extensively by universities all over the world as a source of DOIs and a repository of associated identifier metadata. These DOIs identify resources with a wide variety of types with Text (45%) and Dataset (25%) being the most common. Repositories that focus on Text resources and repositories that focus on a single resource type are the most common.

Repositories that focus on Datasets and include more than 100 items were selected for detailed explorations of affiliations and organizational identifiers, critical elements in identifying connections across the global research community. Author affiliations are included in 79% of the sampled repositories and 35% of the records in those repositories. Organizational identifiers are more unusual, included in 46% of the repositories and 30% of the records.

Affiliations and identifiers are critical for building a connected research community across the world. The contribution made to that connected resource for University datasets in DataCite is limited by the paucity of the required organizational identifiers. The identifiers that do exist are primarily for the institutions hosting the registered datasets, making them most useful for tracking the contributions made by each institution. Identifiers for collaborators are still relatively rare, making it more difficult to track connections between institutions.